Research interests

The cosmic microwave background signal

You always see things in the past! This is the unavoidable consequence of the finiteness of the speed-of-light. While this fact is completely negligible in our daily life, it has an enormous impact on astrophysical scales, such that stars and Galaxies are seen as they were long ago in the past history of our Universe (ranging from ~8 minutes for our Sun to some 13,4 billion years the oldest Galaxies). One can thus legitimately wonder how far this game can be played. The answer is given by the cosmic microwave background (CMB) signal, which is factually the oldest observable light in the Universe, visible over the whole sky. It depicts the early Universe as it was around 13.8 billion years ago, some 380000 years after its birth (the primordial singularity). All matter was then in the form of a hot and dense plasma. This state can be understood in the framework of the Universe expansion: going back in time and reversing the expansion who is diluting all the matter, its content had to be much more densely packed! The CMB signal is thus a gold mine for cosmology as it allows both to investigate the physics at play at very early times and the evolution of our Universe as a whole.

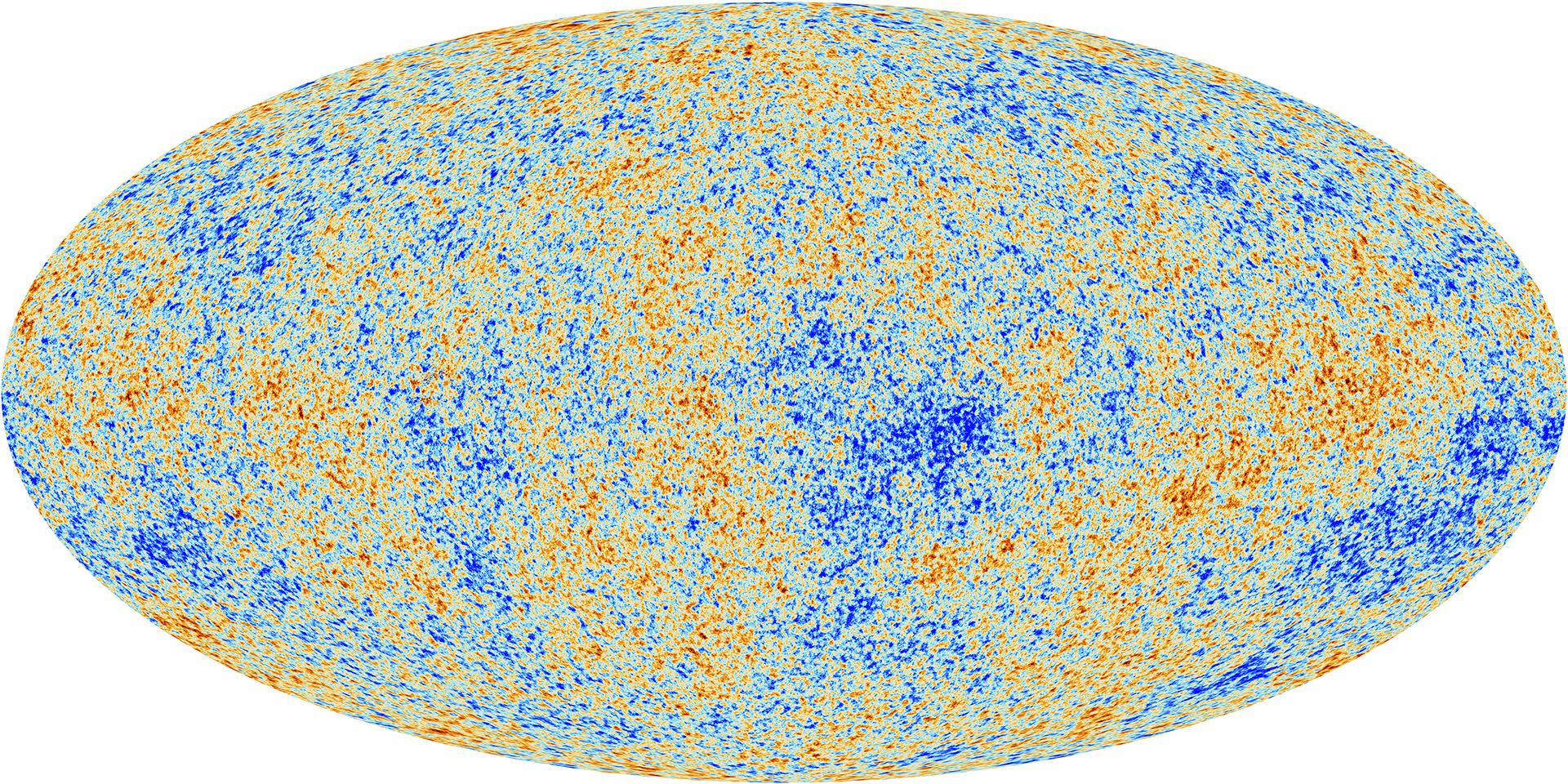

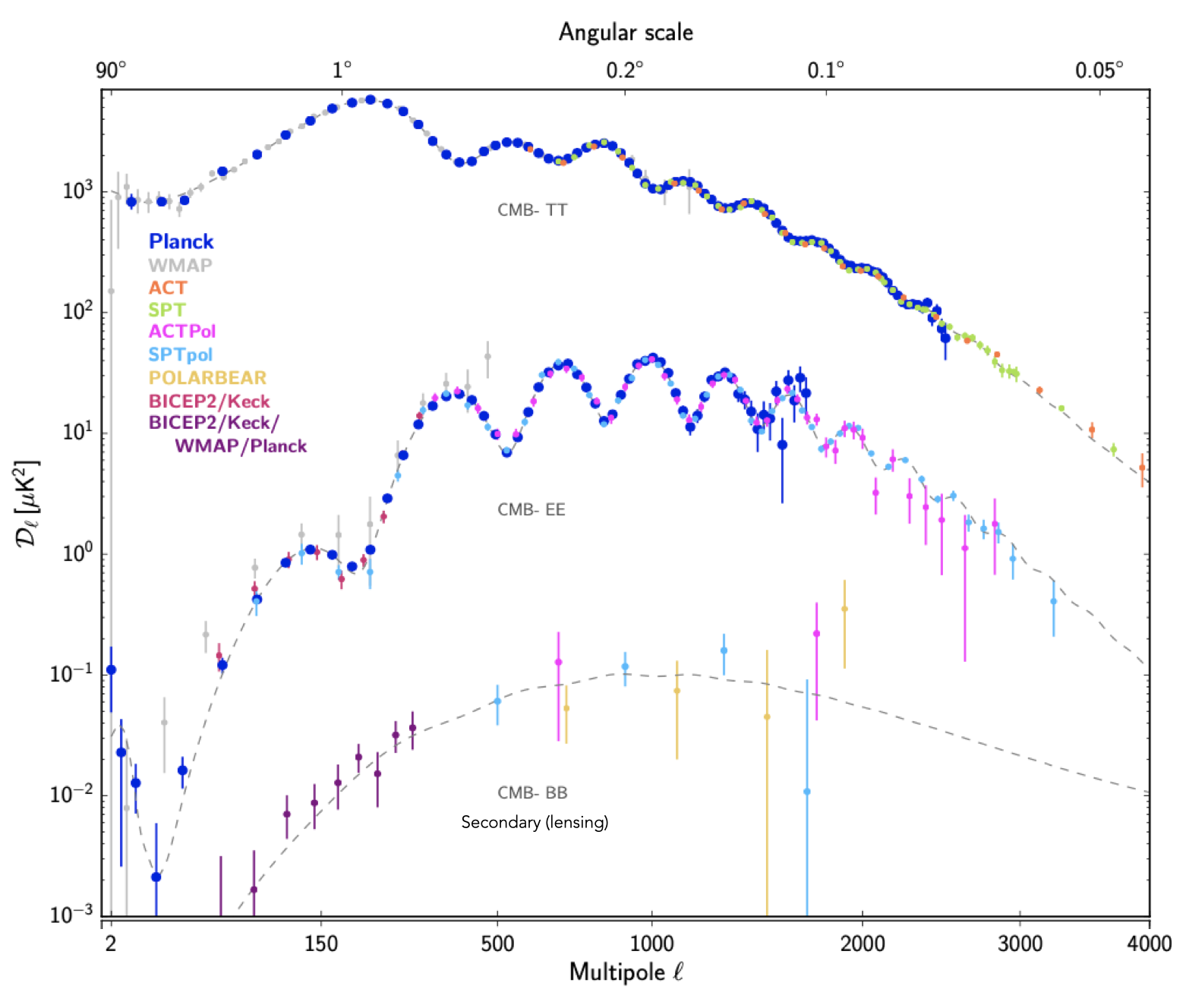

Left: The anisotropies of the CMB signal as measured over the whole sky by the Planck mission (in intensity) Right: primordial angular power-spectra of the CMB as measured by various missions [Planck 2018I].

The CMB was emitted when our Universe cooled down enough for the first atoms to form (event known as recombination). In a dense plasma, the constant scattering of photons on free charged electrons makes it completely opaque. The formation of the first atoms, electrically neutrals, allowed the photons to propagate freely and the Universe became suddenly transparent. The CMB presents itself as a blackbody radiation (characteristic of thermal equilibrium) with a mean temperature of $\bar{T}\sim2.73\, {\rm K}=-270^{\circ}\,{\rm C}$. Going back in time, this would correspond to a temperature of $\bar{T}\sim 3000\,{\rm K}=-2700^{\circ}\,{\rm C}$, hence very hot (for comparison the Sun’s surface is at $\sim 5500\,{\rm K}$). One of the most striking properties of the CMB signal is the incredible homogeneity of its temperature. Across the sky, the variations (inhomogeneities) of $T$ are of the order $\delta T/\bar{T}\sim 10^{-5}$ (see picture above). This means that, at very early times, places of the Universe distant by $\sim 28$ billions of light-years where (almost) exactly at the same temperature.

But the most exciting physics to be discovered yet might hide in the so called polarisation of the CMB signal. As an electromagnetic wave, light is not only described by a number (its intensity) but also by a preferred direction of vibration : its polarisation. While faint and challenging to measure, the CMB signal is significantly polarised. Today, we are looking for the existence of a specific pattern in this polarisation, the so-called primordial $B$-modes, signature of the presence of gravitational waves in the primordial plasma. If detected, they would be interpreted as leftovers of a violent phase which occurred in the first fractions of seconds in our Universe’s history: the cosmic inflation. Inflation was invoked as a mechanism required to explain several puzzles about the early Universe, as the extraordinary homogeneity witnessed in the CMB. Proving inflation would not only refine the understanding of our cosmic origins but also indicate the existence of new physics, yet to be discovered, at the origin of inflation.

The Foregrounds challenge

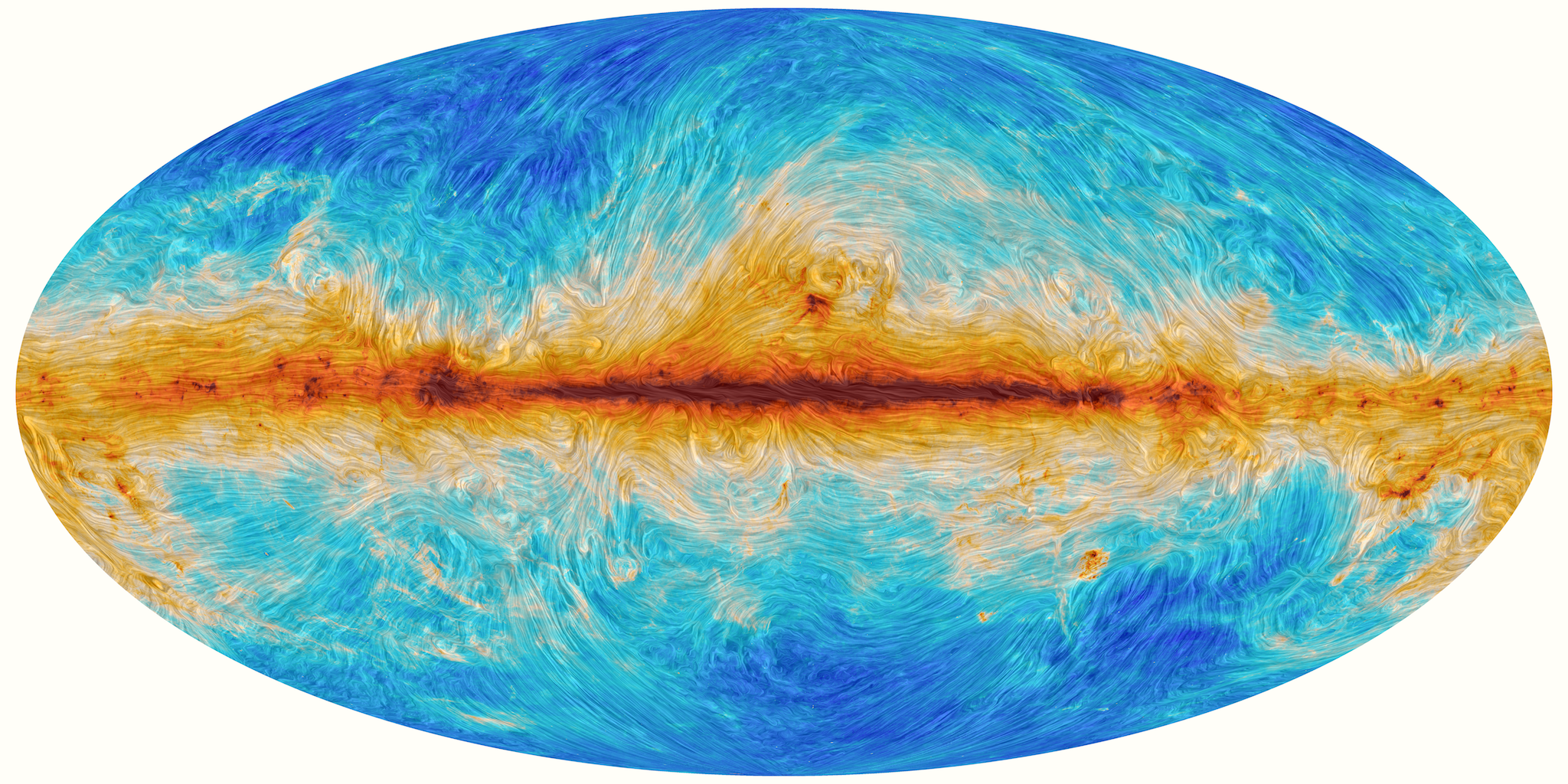

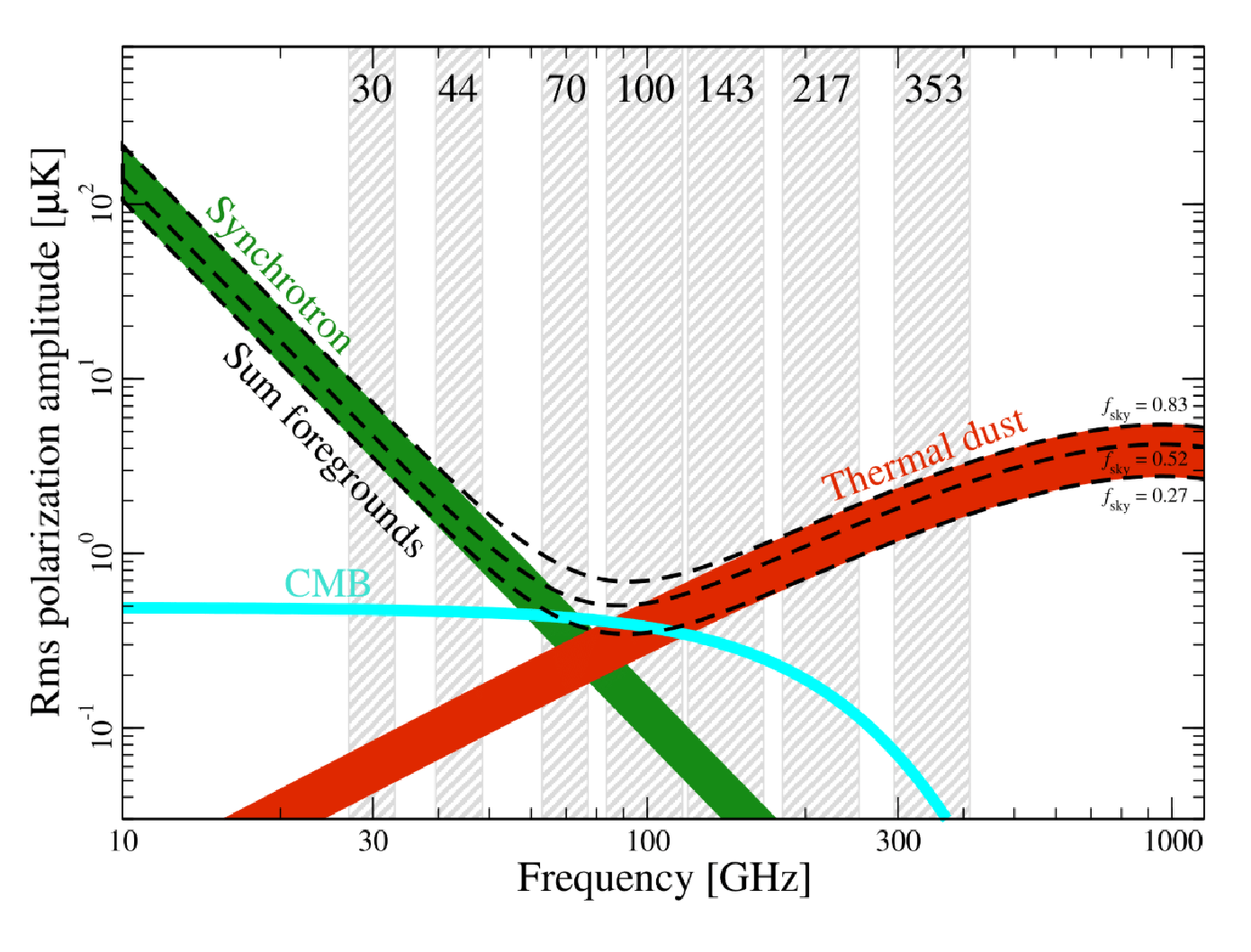

Left: Galactic magnetic field traced by the dust polarized signal from Planck data at 353 GHz Right: Rms of the polarized amplitude of foregrounds compared to the one of the CMB [Planck 2018I]

Mapping the CMB polarisation over the whole sky in the quest for inflation represents a thorny challenge. Part of the reason why comes from our location in the arm of a spiral Galaxy: the Milky-way. Indeed, due to our position in the Milky-Way, any large scale observation of the sky is dominated by the signal of our own Galaxy. This can easily be noticed by the presence of a gigantic white “cloud like” band when looking at the sky during a nice and dark summer night. The presence of such a signal is a major roadblock for CMB observations, as the Galactic signal is polarized and much brighter and complex than the CMB signal in the microwave: we talk about Galactic foregrounds. In polarisation, they are due to two main sources:

Dust grains, re-emitting the light from the nearby stars which heat them. The grains are elongated and rotating perpendicularly to the Galactic magnetic field. They are omnipresent in the interstellar medium and we know that they play a crucial role in star formation and astro-chemistry.

Synchrotron emission emitted by light charged particles emitted from hot regions and spiralling around the Galactic magnetic field. Foregrounds produces a large amount of $B$-mode signal that can easily be confused with the signal of primordial inflation in the CMB. As such, one has to carefully understand the signal of our own Galaxy in order to remove it and analyse the CMB signal.

Cosmological surveys and missions targeting the CMB

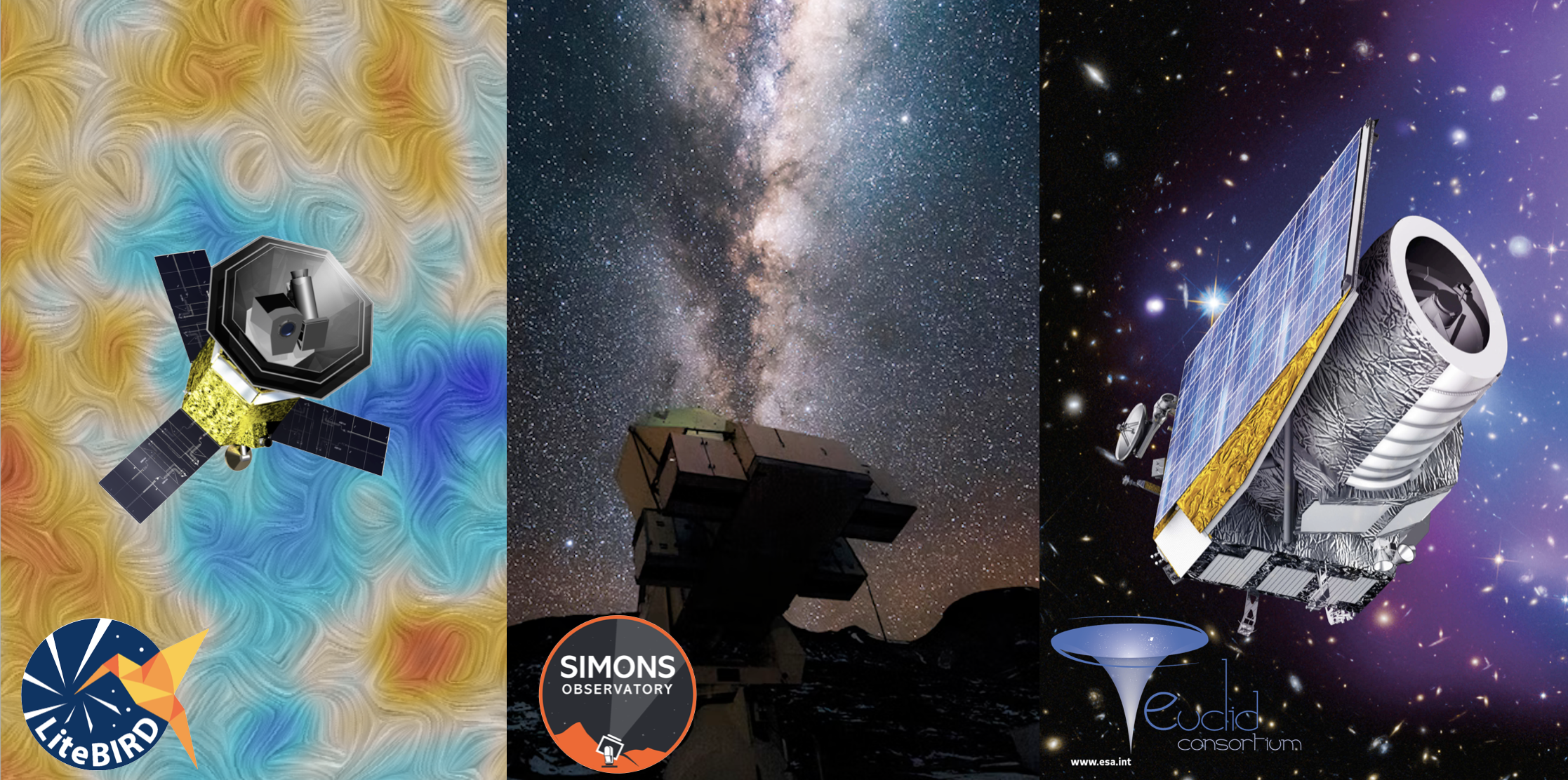

Numerous projects are ongoing or will be deployed in order to target the CMB polarisation. They will be observing both from the ground, using large telescopes or from space, with satellite missions. I am currently involved in two such major missions:

The Simons Observatory (SO) is a ground based CMB experiment under construction, located in the Atacama desert, in Chile.

The LiteBIRD satellite is a CMB space mission proposed by the JAXA. It is expected to be launched in 2032.

Moreover, large cosmological surveys targeting other observables than the CMB, can teach us a lot about the structure and the physics at play in our Universe. Their data can be used together with CMB data, providing a blissful synergy for cosmology. In this framework, I am also a member of the Euclid consortium, aiming to investigate the nature of dark energy and the possible connections that can be made with the CMB data.

All the papers I co-authored in the framework of these collaborations can be found here.

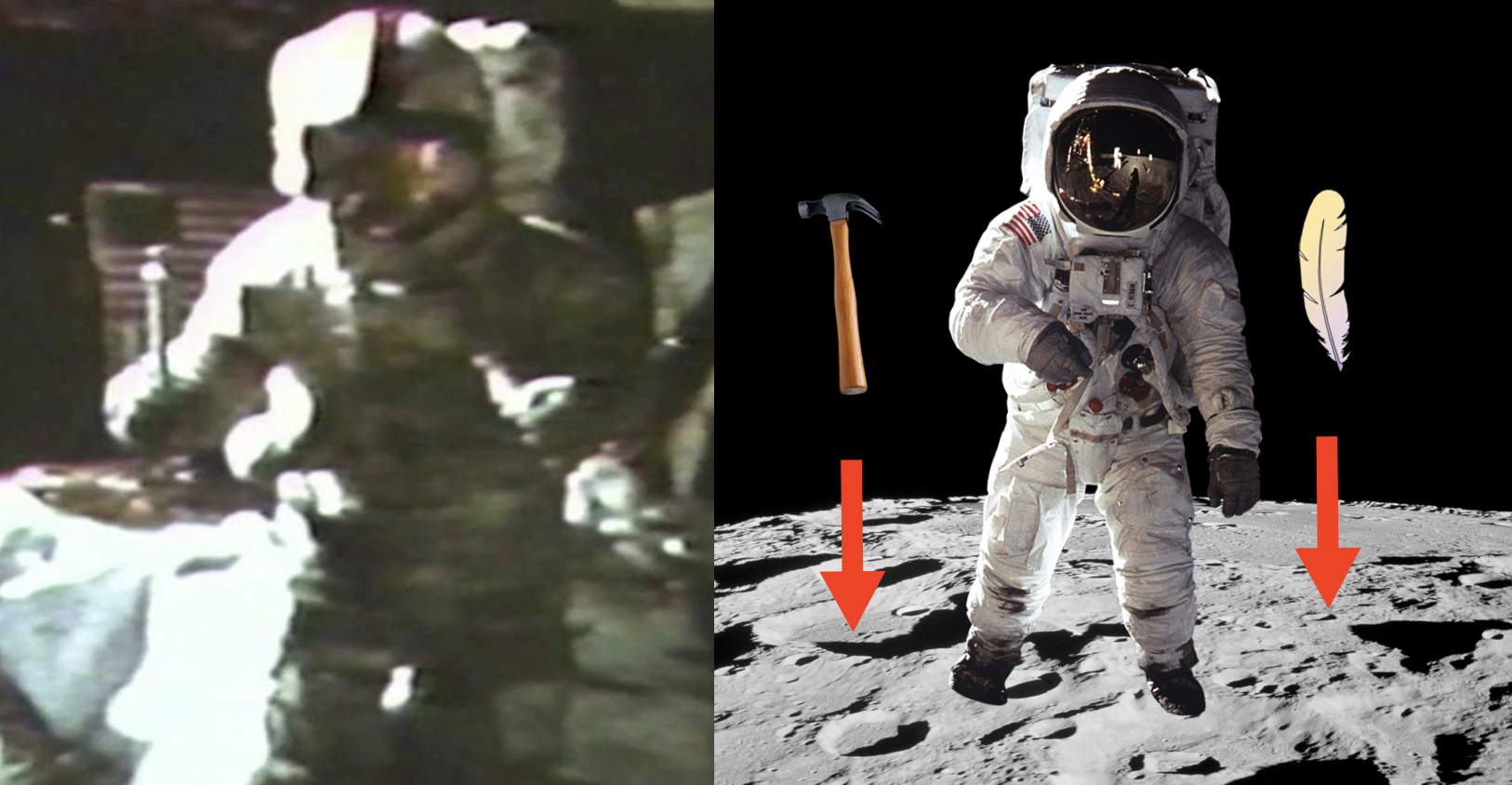

Theories of gravity and fundamental constants

Studying the Universe and its evolution also allow us to inquire about the fundamental laws of physics. In particular, one can test for possible extensions of our theory of gravity, by looking at how this force acts on the largest scales. Our current theory of gravity is given by the general theory of relativity, describing this force as the manifestation of a curved space-time in which objects move in a geodesic motion. A elementary building block of general relativity is given by the Einstein equivalence principle (EEP), stating that all bodies should fall identically in vacuum, independently of their shape and composition. We are not necessarily familiar of this principle in our daily life, due to the presence of air friction which slow down the fall of the objects. However, as it has been tested on the moon (see illustration above), this principle holds in the emptiness of space. Its validity is currently tested up to an extreme level of precision ($10^{-15}$) with some experiments as MICROSCOPE. It is thus of first importance to investigate this principle and quantify the impact of the current limits on its violation on possible alternative theories in which it is expected to stop being true.

\

\

Left: Original picture of the test of the equivalence principle by Apollo 15 in 1971 Right: Sketch representing the experiment.

In my work, I investigate the consequences of our best measurement of the EEP by using its synergy with another perhaps unexpected observable: the value of the fundamental constants of nature. Besides gravity, our other best current theories of physics, the gauge theories, describe the fundamental forces as quantum fields inhabiting other curved abstract spaces (fiber bundles). All these theories require some numbers, called the “fundamental constants”, which can not be explained by the theories themselves, but only measured. Surprisingly, their values seems incredibly well adjusted to allow for chemistry and life to appear in our Universe i.e. changing them very slightly would completely transform the Universe as we are experiencing it. As such, the value of the fundamental constants represent one of the biggest mystery of contemporary theoretical physics. A fundamental quest is thus to investigate whether or not these values could have been different. We can do so by using telescopes to probe them in very distant regions of our Universe, both in space and in time. Discovering that their values could be been different somewhere/sometime else would be a direct (model independent) proof for the existence of exciting new physics at the origin of this variation.

Quite amazingly, a space-time variation of the fundamental constants of nature must also induce a violation of the EEP, such that testing the stability of the fundamental constants in the Universe also allow us to test the validity of general relativity and vice versa! In my work, I explore models of new physics in which both variations of the fundamental constants and hence a violation of the EEP are present. I confront these models with CMB and other data in order to derive the latest to date constraint on their parameter spaces. This is for example the case of string theory models, in which gravitation and all the other forces are unified within the same framework and all the particles of the Universe are understood as microscopic vibrating strings.